INTERVIEW BY KENNY KANG

William (Bill) Bonvillian is currently a lecturer at MIT in the departments of Science, Technology and Society and Political Science, as well as a Senior Director of Special Projects at the MIT Office of Digital Learning. From 2006-2017 he was the Director of the MIT DC Office. He sat down with Kenny Kang, SPI’s 2018-2019 External Liaison, to discuss his career and his role in SPI’s history.

Kenny Kang:

Before we delve into things related directly to SPI, I just wanted to ask how you were initially hired on to be the director of the DC office as some background.

Bill Bonvillian:

Sure. You know, I'm actually trained as a lawyer and practiced law. Then I became, early in my legal career, deputy secretary of transportation and director of congressional affairs with the US Department of Transportation; I went there because I was interested in policy. I worked at that time on all the big deregulation bills Congress was passing. I worked on the Chrysler bankruptcy legislation, and how to salvage the US auto-industry. It was a great policy experience. And I did a lot of work with Capitol Hill. So, after a number of years of practicing law after my transportation job, a good friend of mine got elected to the US Senate. Somebody I' worked for in the past, and I had one of these classic Capitol Hill conversations.

I got a call that said "Bill, why don't you come on up and meet me in my office? We'll talk." Well, that conversation actually went on for the next 15 years. I thought I'd do it for a couple of years, but just couldn't resist staying. The work was just too much fun, too fascinating and I was involved with big issues and problems that I really cared about in a way that you just can't do practicing law. I was not unhappy at all while practicing law, but you just can't do policy while practicing in the same kind of way. So that was a fascinating experience. I began gravitating in the course of my work as a legislative director and senior legislative advisor more and more towards science and technology policy and was involved in, you know, I'd say frankly, virtually all of the major legislation moving on S&T policy through the Senate and the Congress in general in that 15 year time period.

And these issues fascinated me. I had first gotten involved in the implications of technology and really looking at the US auto-sector and what was happening to it. I did a lot of work on R&D issues in support of the Senate Armed Services Committee; I got to know the DARPA model well, and how different that was from the historic agency pipeline model. I learned all those lessons from the agencies pretty well, and learned the S&T policy process well, during the course of that congressional experience. I did a lot of other things too. I worked on creating the Homeland Security Department, worked on creating intelligence reform legislation and the Director of National Intelligence. But as part of those, I would always have an S&T policy role. I also helped create an ARPA within homeland security (HSARPA). So it was a deep dive into S&T policy.

And MIT in that time period had created a program of bringing senior congressional staff up for a three-day, intensive seminar at MIT around a key policy area that was deeply tied into science and technology. And those were fascinating explorations across a wide range of activities. I got to know MIT as part of that process. I was up for five or so of those over the years, and found them very intriguing and developed a real affection for MIT. In the process I got a real sense of what it was like. Chuck Vest, who was president of MIT in that time period, had always spent time with congressional staff, so I got to know him - a remarkably impressive guy. So when a job at MIT opened up to direct their Washington office, I figured I’d get to work on all the issues I was really deeply involved in, and I'll get to do that full time. So I applied, took that slot, became Director of the Washington Office in, 2006 I believe it was, and was hired by Susan Hockfield who was MIT's incoming president.

Kenny:

Well, thank you for that introduction, and I think that segues pretty nicely into my next question. From my interpretation of events, it seemed like you were involved with SPI from its very early beginnings, which I believe coincided more or less around when you started, at the MIT DC office. So from your perspective, how did SPI get started and at what point were you approached to start building that relationship that we've been so fortunate to have, and has been really instrumental in SPI's growth in the following years.

Bill:

That's kind of a fun story, one of my favorite MIT experiences, because it's been very important to me as well, a source of real pleasure. So Susan Hockfield is the new president of MIT, and a very talented, very able person and a terrific MIT president. Susan wanted to stay in touch with students and she had adopted an approach of having breakfast with small groups of students. So she really talked to them and found out what they were thinking on a weekly or bi-weekly basis, as she could. So at one of those meetings with students, she had a meeting with an MIT graduate student named Alicia Jackson. And I got an email, you know, like the next day from Susan. And the email is essentially along the following lines - "Bill, I had breakfast with MIT students. I had a lengthy discussion with one of those students, Alicia Jackson. Alicia expressed great concern about the fact that MIT students were getting graduate degrees and going into the science and tech fields, engineering fields and they didn't know - they knew their science, they knew their engineering really, really well - but they didn't know where these organizations came that were going to have to provide their R&D support.” They didn't know what their history was. They didn't know what their policy perspectives were. They didn't know what role they played in the system. They weren't taught the big picture of the system that they were going to spend their lives in. And it was kind of a black box. They knew what the grant application process was, but they didn't really have a perspective on how these institutions operated. They were kind of left in the dark. I'm extrapolating a bit from later conversations with Alicia, but that was the essence of Susan Hockfield's message. So her directive to me was “the next time you're on campus, please meet with Alicia and see how you can contribute since after all you understand how this system works.” I said, sure. And sure enough, I emailed Alicia, and we set up an opportunity to have coffee, and I got pulled into a conversation with her and she began asking me all kinds of questions, queries in a very tough-minded kind of way. No nonsense. "What's this, how does that work? How's that connected with where it is? How come you know all this stuff? What's your background, what's your experience?" She managed to get out of me the fact that I'd been teaching for four or five years at Georgetown, of course, on science and technology policy there. And when she found out that I was already teaching and had already organized a full semester large course on this topic, and was teaching it, the conversation went on as, well, "why don't you teach that here?" I said, I can't possibly teach that at MIT, I've got to be in Washington.

And I was new to MIT, so she said, "well, haven't you heard of IAP?" And she explained it to me, a month-long short semester in January. And she said, well, you'll teach it then. I said, well, I can't come up for a month, I've got to be in Washington. And she said, no, no, no. You'll teach it for a shorter period of time. You know, fine, that was her idea. But I was skeptical. I thought, fine, this idea will fade. I had my meeting, I emailed Susan back, following up on my meeting with Alicia. And a little time passes. And then I get a message from Alicia with a number of other MIT email addresses on it, and the message says, "When are you next up on campus? I want you to meet with The Committee." It was kind of unexplained. But I said, sure, I'll meet with “The Committee.” And sure enough when I went back to MIT, there was a group of about five MIT students, grad students, who were intensely, along with Alicia, pursuing this subject of setting up a short course during IAP, and they persisted in this. And I said, look, I don't have time to organize a whole course, I've got more than a full time job. So you're going to have to organize this. I'll show up and I'll teach and all that. I've got a really big curriculum that I've been teaching at Georgetown, but I'll turn it on its head and turn it upside down and rethink it to organize a short course and a syllabus around it. And they said, fine, you do that and we'll organize the course. And sure enough, much to my utter amazement, they did. And it was an early lesson for me on MIT and its culture.

The lesson was, if you want to get stuff done at MIT, the students do it. So always involve them in whatever you're up to at MIT because they'll provide tremendous dynamism and energy for organization. And that consistently proved to be the case on many things I've worked on at MIT, in my 11 or 12 years working in the Washington office. So anyway, that began the “Bootcamp” course. But we were concerned about what the “come-on” to the course was going to be (why students would be interested). So I had suggested to them that, gee, let's offer in the spring a program where the MIT students would come down to D.C. to learn about how Congress works, and we would work with them on organizing (the Washington office and I), over a two day trip to Washington.

I had been involved in a long standing effort, led by a series of science organizations, called Congressional Visits Day. And it brought in experienced scientists and engineers, but not students. We brought them in for two days in a very organized way to lobby Congress, meeting with congressional staff and members to support federal R&D funding in science and technology areas. I knew it would fit into the Visits Day program, except MIT would send a student delegation rather than a company sending three or four scientists or science organizations sending groups of scientists from different states. So we pledged that we would put that together as part of the come-on to build interest in the Bootcamp course because we weren't sure that anybody was going to be interested in that alone.

So the students advertised the course widely that year. This is 2007, and then we certainly hit a big problem, which was a good problem. The response to the request to join the course was overwhelming.

One of the solutions was saying in the application, if you want to join the course, you have to write a multi-page essay about why you want to be in the course. And we thought, well nobody's going to write an essay to get into a course, but sure enough, students did and it was still totally over subscribed. So, you know, the students were in charge of this. They had to make the cut. So they did and that’s how the first Bootcamp began.

I think it went really quite well. And you know, fortunately I had a substantial amount of experience by now in teaching. And then from my 15 years on Capitol Hill working with the R&D agencies, I knew what the federal R&D system was and I had a significant perspective on international as S&T organization, because of my involvement in these issues in my congressional jobs.

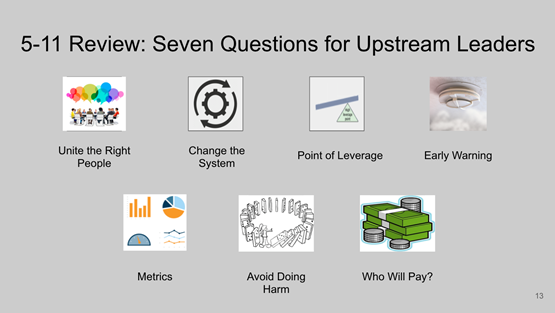

So, we put together this multifaceted course essentially on science and technology policy, and its main theorists and thinkers in innovation policy from the economic side, on international S&T policy and organization side and with a strong focus on how S&T was organized. I spoke at the institutional level, but also discussed what R&D advances look like in terms of the teams and great groups at the face-to-face level. And we did case studies, particularly in areas like the life sciences. And then we focused on what the DARPA model was versus the NSF model, for example, and had case studies in energy for which there was strong interest. Susan Hockfield had started a big energy initiative on MIT’s campus so lots of students were interested in that. So the course went off well.

But then I was approached by “The Committee," and was told that there were a lot of people really angry that they didn't get into the course. And so I was going to have to teach it again. They said, look, you're going to have to give it again in the spring just for the people that were upset since we don't want to start our organization by creating a community that's aggravated. They said, look, we got a solution to that problem. We'll give it over Patriot's day weekend, and don't worry, Patriot's Day weekend is a great MIT student break time. No one's going to apply to take it. Then you won't have to give it. Well, needless to say they were wrong so I had to give the course again in the Spring and you know, at that point we vowed, let's not advertise. Let's not make that mistake again. Let's rely on word of mouth in future offerings.

But that began the program. And then the Washington office worked with “The Committee" to organize that spring Congressional Visits Day (CVD) in coordination with the science organizations' efforts to bring in scientists to lobby for a day. You know, that was fascinating. We got a group of 20 or 25 MIT students who had taken our course, and therefore had a whole background in S&T tech policy. And so they were ready for this. They knew what story was, what the broad picture was, and the committee did a lot of really good organizing to get the students prepared for what they were going to do.

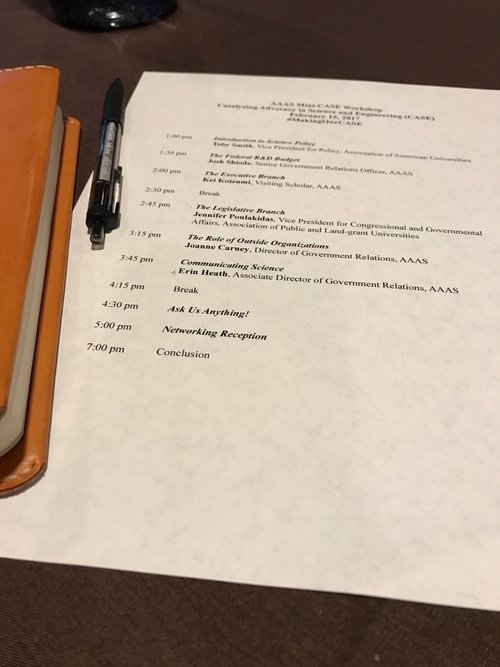

The MIT Washington office and I put on quick course in advocacy. How do you do it? How do you lobby Congress? How do you make your case? You walk in with a one page document that states your case in what you want and need. You never go into a congressional office without an “ask.” All those kinds of fundamental lessons of lobbying we taught in kind of a multi-hour seminar. So the students came down to the Washington office. And then they would participate also, in broad presentations on the issues that were held at the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). And then they themselves organized meetings on Capitol Hill with many congressional offices. So that's where CVD came from, which is a second main-stay along with the S&T policy course, of SPI. And the committee of course became SPI. And, you know, it's been a thriving and fascinating organization I've been delighted to be associated with since then.

Kenny:

So at what point did Executive Visits Days (ExVD) start? That was my first big SPI event and I thought that provided a great framework to then sit in on your bootcamp and then attend the following CVD that I was a part of.

Bill:

Only a limited number could come on CVD because the cost of flying students down, but SPI had gotten great at raising money from deans and MIT administrators. Frankly, if you're a dean of science or dean of graduate students, and a group of students walk in and say, “Hi, we'd like funding so we can understand S&T policy and organize ourselves to go down and lobby Congress for science support.” You know, how could you say no? These were all issues about science support, that were real national issues, real issues for the future of science in the US. So the deans found this an incredibly appealing pitch and have been willing to provide support for CVD since then.

ExVD came about in part because it was important to have a perspective on what the Executive side was, after learning about the innovation organization system during Bootcamp. You know, wouldn't it be important to visit the Executive branch agencies and get a sense for what they were like?

This all coincided in a period of time when fewer students were actually going into academia although their education in many ways was geared towards an entrance into that career path. But smaller numbers of jobs were opening up. So students were going to leave with PhDs and graduate degrees, but were going to need to go do other things. And you know, what kind of careers were they going to have? So careers in science and technology policy became an increasing interest at MIT in this student community. So that was another motivation to start ExVD.

And you know, we could organize those meetings, too, because in the Washington office, our job is working with those R&D agencies. And frankly there were MIT alums in almost all of them, who were happy to spend time with MIT students. So working with SPI, this became another piece in the puzzle, a programmatic puzzle that is now key.

Kenny:

From my perspective, the core driving force of SPI has been consistent throughout the years, but in what ways have you seen SPI change or grow that you were either surprised by or pleased to see?

Bill:

I think one of the more impressive things SPI has done, is that it organized a science policy certificate program at MIT. You know, this wasn't my doing, but I was delighted to watch and provide some assistance. This was when Johanna Wolfson was leading SPI, but there was a whole team of folks deeply involved in this effort. I mean, the idea was a simple one, you know, there was a whole group of policy courses spread in various places around MIT that you could actually organize into a more coherent framework for graduate students that wanted to come out of MIT, not only with their graduate degrees, but secondly, with a certificate indicating they had background and perspectives in science and technology policy. And there was a sense that students wanted to go into S&T policy and that they might well have an interest in having a certificate indicating their background in it, not only a traditional, rigorous science and engineering background.

So the student group organized SPI around this and they created a faculty committee. There were some faculty at MIT strongly interested and supportive of that kind of programmatic element at MIT. The faculty committee was very supportive and really worked with the students, and the SPI group assembled a list of policy courses in MIT and began to put together kind of a menu approach. The Bootcamp course that I had taught then would be kind of a framework introductory course that was a requirement for the certificate program. Then there would be a series of other policy courses around MIT that grad students could take based upon their interest and fields, whether they were in energy areas or economics, etc. And that I think has really been a real contribution to grad students that might want to pursue policy careers.

Kenny:

So are there any specific notable events during SPI’s history that stand out to you?

Bill:

One CVD memory sticks out. Senator Scott Brown, a senator from Massachusetts on the Republican side got elected in somewhat of a surprise election win. He was delighted to meet with the SPI students when they came down from MIT during one of these congressional visits days. And the students had a meeting with him when he was brand new to the Senate, and very concerned about federal budget deficits.

The students went in and met with him and made a pitch. I was sitting at the back because sometimes we from the Washington Office sit in on some of the Massachusetts meetings to see what's on the members' minds. And Senator Brown's response to the pitch from the students about increasing science R&D spending, which, you know, is fundamental for US economic growth and economic wellbeing – Senator Brown said, “Look, I'm worried about the budget. I can't necessarily make that kind of commitment. We got an out of control, budget deficit to manage.” So the students were concerned and they went on and made their case. You know, they cited Robert Solow and said we'll have technological advances, economic advances for wellbeing in the US etc. They had their case down but Senator Brown wasn't there.

So the students were concerned about this. This is Massachusetts, a very strong science state. What do we do? So we had a chat afterwards and I made some suggestions, but the students had the heart of the idea. They decided, Senator Brown may not listen to university students, but he sure listens to the business leaders. So let's make connections with the business groups in Massachusetts, which overwhelmingly, frankly, support science and R&D spending because there are many advanced tech companies that just completely rely on it.

So they met with the Mass Tech Alliance and the head of the Mass Tech Alliance at that point was Ray Stata, an incredible MIT alum, and also on the executive committee of the MIT Corporation. I wasn't in these meetings, of course the students did them and organized them, but you know, I was told later that Ray was totally on board this idea. And the next time he met with Senator Brown, he made a strong pitch for science and technology R&D support. And other business groups joined in.

And there was pending legislation at the time, called the America Competes Act to increase science funding and it was up for reauthorization. And it had been supported by some stalwart backers of science in the Senate. But Senator Brown was not a cosponsor when it came time for this bill to come to the floor. I was watching, on CSPAN, the floor debate, and sure enough Senator Scott Brown rushes down to the floor and announces that he wants to be added as a cosponsor to the legislation that's going to support strong increases in R&D spending.

And then he proceeds to deliver a strong endorsement of R&D support as critical to American growth and the fundamentals of our economy and a strong tech sector. It was an impassioned talk. You know, SPI working and meeting with his office in Massachusetts and sending them materials and meeting with the business groups really helped bring about a change in Senator Scott Brown and changing his fundamental attitude towards what the value and importance of S&T investments is.

So that was just a fun episode. It underscored for the SPI students that you can't just hold one meeting with a member of Congress or staffer. You got to have follow up and you've got to have allies that can give you continuing support. It was a great case study in the advocacy process for the students that time.

Kenny:

Yeah, that's an amazing story. If you want to make any closing remarks, we’d welcome them, but otherwise, thank you so much for your time and for this conversation.

Bill:

What I've been fascinated by watching (and I've been a little involved in it), is the spread of SPI-like organizations around the country. SPI was really the first. After some years it began working on trying to be helpful to students in other universities that wanted to form similar organizations. And frankly that's now become a national movement and it's got support from the AAAS, it's got support from the American Association of Universities and there's now SPI-like organizations in a number of American universities. And the University of Virginia, which has an SPI that I've been in touch with over the years, they've now raised foundation funding to create chapters and organizations of SPIs like this around the country. So SPI has a tremendous amount to be proud of. It's really initiated a whole focus on science and technology policy among students, graduate students in particular but with undergrads as well, and building awareness and understanding for what this whole S&T system looks like and operates and how to run it. So SPI has been an amazing organization to watch and the energy and dynamism of the students is just always a pleasure.