March 12, 2017

Written by Kenny Kang

The American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), a professional society founded in 1848 with a core mission to “advance science, engineering, and innovation throughout the world for the benefit of all people,” hosts biannual meetings, which focus on different themes. To the benefit of those of us at MIT, the Fall 2017 meeting was hosted at the Hynes Convention Center in Boston, and to the interest to those of us in the Science Policy Initiative (SPI), the theme was “Serving Society through Science Policy.”

A distinction that may not be clear for those just starting to think about becoming involved with science policy is the difference between “science for policy” and “policy for science.” The former refers to conducting scientific research or using scientific data to inform policy decisions, whereas the latter is more about how policy making may affect how we do science in terms of factors such as regulations and funding. The two are complementary, yet the difference could determine how scientists enter the policy realm. The conference was a great way for us to be exposed to both sides of science policy and to start thinking about how scientists can fit into it all.

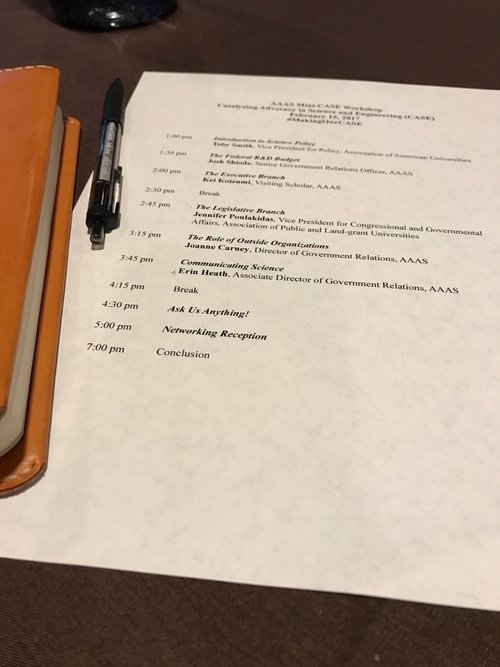

The AAAS mini-CASE (Catalyzing Advocacy in Science and Engineering) workshop, an abridged version of AAAS’s very popular annual multi-day workshop, provided a big-picture of where science fits into the policy making process in the federal government. The session organized by SPI, “How Early Career Scientists can Serve Science through Policy,” brought together a panel of career scientists who have also stayed engaged and made an impact in science policy. The session “Community-Scientist Partnerships: Bridging the Gap between Communities and Science,” exposed attendees to feasible avenues of getting involved in our communities by inviting those with experience engaging in science policy at the local level.

Despite the breadth and diversity of the sessions at the conference, there were recurring themes that should be highlighted as take-home lessons when it comes to becoming involved in science policy.

Learn to communicate

As scientists, we get very comfortable speaking with other scientists. We use scientific lingo to communicate our work to others, and especially in a “bubble” such as Cambridge, this can quickly become seemingly normal. However, we need to realize that the vast majority of the country, especially those in Washington D.C. do not speak the same way, so we need to adapt how we communicate based on our audience. This issue was highlighted very clearly during one of the sessions, when one of the speakers used the word “uncertainty” as an example. For those of us in science, regardless of the field, the word “uncertainty” is fairly harmless and is accepted as a part of our work. However, to those outside of science, the very concept can be difficult to grasp and accept.

It is not only specific words, but also the structure of how we communicate that we need to adapt. When it comes to presenting our work, scientists first start with relevant background, go into the data, and finally present the conclusion; in other words, it starts broadly and narrows in focus. Policy makers want the reverse. They first want the bottom line, followed by the topic’s relevance and the details.

Get educated on the issues

Unfortunately for scientists, science is not the only issue that is considered in the policy-making process. Regardless of how strongly we feel we have made our case with and for science, policy makers must weigh many other factors such as economic, social, and demographic implications, among others, when making decisions. Therefore, it is critical that scientists are also educated and become at least somewhat literate in other areas that impact policy-making. Showing how science fits into the bigger picture will be more effective than simply saying “science is cool, science is important.”

Get involved (early and locally)

One lesson that was highlighted many times was to make ourselves available. We don’t need to go to Washington to make an impact. Visit your representatives’ local offices where their schedules are more amenable to meeting with you and put your name out there as a resource as someone they could contact if they had relevant questions.

Several panelists also stressed the importance of getting involved at the local level and visiting state representatives. People often overlook what happens at the state level, but what happens locally can have significant effects on science policy. In addition, forming relationships locally can lead to having allies at the federal level when they then move on to Washington.

As graduate students, it is easy to get tunnel vision and only see our work within the scope of what did or did not work from one day to the next. The AAAS conference was a refreshing reminder of the bigger picture, and a realization that there are many available avenues through which we can begin making an impact.